Some beliefs are inconsistent with each other. If you hold one of the beliefs, then you can’t hold the other. For example:

- The number 5 is less than the number 10.

- The number 5 is not less than the number 10.

But people often think that beliefs conflict when they really don’t conflict.

In a moment, we’ll get to a case that’s done great harm to society. But here are a couple of simpler examples to illustrate the point about beliefs that don’t conflict:

- This apple is red.

- This apple is round.

Those two beliefs are different, but they don’t conflict because they’re about different qualities of the apple. One belief is about its color, the other about its shape. And how about this pair of beliefs:

- John is wearing a hat.

- John is an accountant.

Again, there’s no conflict. Wearing a hat has nothing to do with being an accountant. Both beliefs can be true, even though they’re different.

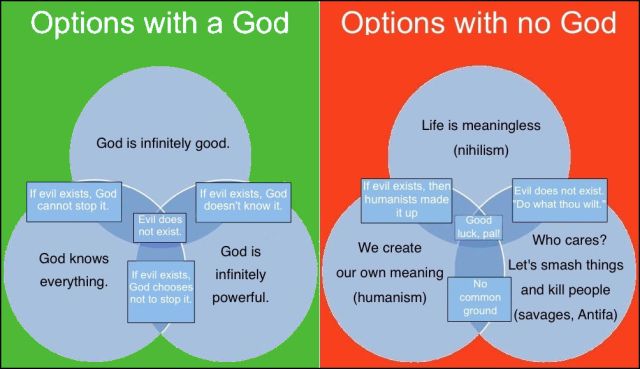

Now consider the harmful case. Many people think that these beliefs conflict:

- All people are equal in human dignity and human rights.

- People vary widely in their character, behavior, and abilities.

Most people know that the second belief is true, but they’re reluctant to say so because they think it conflicts with the first belief.

That’s why they pretend to believe that any disparities between identifiable social groups must be caused by something nefarious. They’re afraid that if they admit any differences between people, they’re denying that some people have human dignity and human rights.

But if they think about it, which they hardly ever do, it’s obvious that the beliefs not only do not conflict, but cannot conflict. The reasons are simple:

- They are different kinds of beliefs, and

- They are about different things.

The second belief is about facts, just like “John is wearing a hat.” You can see John, you can see the hat, and you can see the hat on John’s head. Likewise, you can see that people do in fact differ from each other — both individually and, on average, in social groups. The fact that generalizations are sometimes false doesn’t mean that they’re never true.

But the first belief isn’t about facts, at least not in the same way as “John is wearing a hat.” You cannot find any physical thing or event corresponding to “human dignity” or “human rights.” Those are not facts. They are choices we make about how to treat other people.

To say that someone has human dignity and human rights is to say that you intend to treat him or her in a certain way, more carefully than you would treat things that do not possess human dignity and human rights.

To say that all people are equal in human dignity and human rights is to say that you don’t intend to treat anyone differently based on irrelevant characteristics.

Of course, that qualifier “human” will probably cause trouble someday. We might discover that dolphins are just as smart as we are. We might develop robots that can pass a rigorous Turing test and can behave exactly like human beings. We might encounter space aliens. None of them would be human, but they would be intelligent, self-conscious beings like us. How could we argue that they lack “human” rights?

Like I said, it’s not about facts. It’s about choice. How do we choose to treat other living beings, and why? It’s worth thinking about.

Check out my book Why Sane People Believe Crazy Things: How Belief Can Help or Hurt Social Peace. Kirkus Reviews called it an “impressively nuanced analysis.”