My latest blog post for The Jewish Journal:

“They tried to kill us. We won. Let’s eat.”

According to the late comedian Alan King, that’s the explanation of most Jewish holidays.

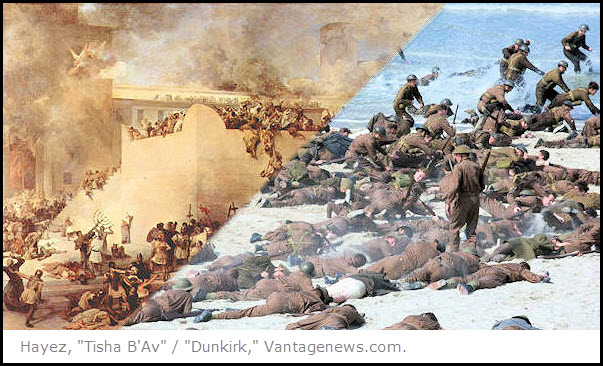

It’s particularly relevant to the fast day of Tisha B’Av, which is a few days from now. On Tisha B’Av, we mourn the destruction of the First and Second Temples, along with other tragedies that have befallen our people.

But this year, the approach of Tisha B’Av has me thinking of — Dunkirk. A big-budget movie about it is scheduled for release next summer.

If you’ve never heard of Dunkirk, or what makes it significant, don’t worry. About half of the U.S. population thinks that World War II occurred shortly after the Civil War. You’re way ahead of the game if you can find France on a map.

In May 1940, the German Army trapped 10 divisions of the British Army at Dunkirk, an area in the North of France that was directly across the English Channel. Hitler ordered the Luftwaffe to destroy the British forces, which had no way to escape from the French coast back to England. If the Luftwaffe had succeeded, Germany might have won the war.

Instead, the British people set sail in their own private boats — fishing boats, cargo ships, rowboats, anything that could make it across the channel and back — to rescue “their boys” from the beaches of Dunkirk. Almost 800 boats made the trip, over and over, under heavy fire from German planes and artillery. They rescued almost 340,000 British soldiers from certain death. Many of the rescuers died in their heroic mission.

By military standards, the Battle of Dunkirk was a crushing defeat. But “Dunkirk!” became a symbol of British people’s courage, unity, and determination to prevail against any odds.

I’m sure you see where this is going. If anything on earth has preserved the Jewish people for millennia, it’s courage, unity, and determination to prevail against any odds. Tisha B’Av, just like Dunkirk, takes something bad and turns it into something good.

According to our tradition, the first tragedy to occur on Tisha B’Av was in 1313 BCE when the Israelites failed to trust God during the Exodus. As a result, they had to wander for another 38 years before entering the promised land. On Tisha B’Av in 423 BCE, the Babylonians destroyed the First Temple, and on the same date in 70 CE, the Romans destroyed the Second Temple. It was on that date in 1290 CE that our people were expelled from England and on the same date in 1492 that they were expelled from Spain.

We must allow tradition a bit of poetic license, since archaeology finds no evidence of the 1313 event and says that the First Temple was destroyed in 586 BCE instead of 423 BCE. Only about 2,000 of us were expelled from England, peacefully, and the Spanish expulsion edict wasn’t issued on Tisha B’Av. The value of a religiously helpful story trumps (pardon the expression) a few minor factual inaccuracies.

Tisha B’Av, just like Dunkirk, shows how a people can turn tragedy into victory by telling a new story about it and giving it a new meaning. Instead of being a weakness, the tragedy becomes a source of strength:

“A story told by English Jews, perhaps apocryphal, tells of a prominent nineteenth-century British politician who was walking near a synagogue on Tisha B’Av and heard wailing coming from inside. He looked in and was informed that the Jews were mourning the loss of their ancient Temple. Deeply impressed, the politician remarked, ‘A people who mourn with such intensity the loss of their homeland, even after two thousand years, will someday regain that homeland.’” (Joseph Telushkin, Jewish Literacy, p. 669)

What applies to groups also applies to individuals. You can turn your personal tragedies into victories by telling yourself a new story about them: a story in which you are no longer a passive victim but are instead a survivor, who suffered but became a better and stronger person as a result.

They tried to kill us. We won. Let’s eat (just not on Tisha B’Av).

I enjoy reading your posts about the Jewish faith and Jewish history. This topic involving the destruction of the Jewish Temples makes me segue into a question I have had for some time, which I hope is not too far off topic.

In what we Catholics refer to as the Old Testament Law as handed down to Moses, there was a centrality to various animal and other kinds of sacrifice. Much of that was done in the Temple. After the destruction of the second Temple and up to today, I had always assumed that those sacrifices were somehow continuing, if only through a small group of elderly decendents of Levite priests in a warehouse in Bayonne, New Jersey or some such place, and that the Jewish people could perhaps vicariously participate in those sacrifices via monetary donations. I have more recently come to understand that nothing of the sort happens, and that the sacrifices stopped upon the destruction of the Temple.

It has seemed to me (as an outsider – or maybe as a lawyer) that if anything defined Jewishness, it was the Law of Moses and good faith attempts to adhere to it, as may be possible in a given age. Which would include at least some sort of minimal hat tip to the prescribed sacrifices. But apparently not? I would love to see an informed exposition on this topic. Of course, if this is too much of a topic to deal with in a comment, perhaps this might provide the basis for a good meaty (sorry for the pun) blog post at some future time.

As always, thanks for your efforts here. And a blessed fast day to you.

LikeLike

Hi, JP — Thanks for your thoughtful and well-informed comment. You’re right that sacrifices stopped being a central part of Jewish practice after the destruction of the temples. Orthodox Judaism, and to a lesser extent Conservative and Reform Judaism, do center around observing 613 commandments defined by the rabbinic tradition. However, since I’m not a rabbi, I can’t give a more authoritative answer to your question. May God bless you as well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for that. I hope my comment didn’t come across as flippant, I dashed it off more quickly than I should have, and it was not intended that way.

I thought afterwards that sacrifices would require a suitably holy place, and could see where without a temple, no such place would exist. And your answer helps me along in my attempts at understanding a few of the ins and outs of Judaism.

LikeLike

Thanks for your answer on this. I hope that my question didn’t come across as flippant – I dashed it off more quickly than I should have, and it was not intended that way.

Afterwards, I thought about it more and figured that sacrifices were probably not possible without a suitably holy place, and could see where without the temple, none would exist.

Your answer helped in my attempts to better understand some of the Ins and outs of Judaism.

LikeLike